Tariffs, Ands, or Buts

A partial review of: The Little Book of Economics: How the Economy Works in the Real World, by Greg Ip (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010)

By Peter Sprigg

April 9, 2025

With President Trump’s tariffs—and the resulting plunge in the stock markets—dominating the news, I was curious to learn more about the subject of tariffs. So I looked up the titles of some books on the topic—and then (being cheap) checked to see if any of them were available at my local public library.

Unfortunately, none of the tariff-specific books were in the library catalog—but one more general book on economics was, so I decided to check it out. The Little Book of Economics is by journalist Greg Ip. I’ll focus this review on the one chapter he devoted to international trade (Chapter 6, pp. 85-101).

Trump’s “Reciprocal Tariffs” Are Not

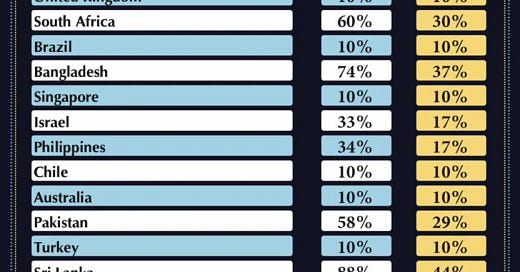

President Trump described his new tariffs on various countries as being “reciprocal” tariffs—that is, we will charge them what they charge us. But as soon as the new tariffs were announced—complete with a detailed chart purporting to show their “reciprocal” nature—economists knowledgeable about tariffs said that the figures shown on the chart did not, in fact, represent “tariffs” charged by other countries.

A “tariff” is a tax a country charges on the value of goods it purchases from another country. The figures on Trump’s chart were calculated largely on the basis of the size of the trade “deficit” with each country. If a country sells more goods to the United States (U.S. imports) than that country buys from the United States (U.S. exports), that is called a “trade deficit.” President Trump, however, called it a “tariff”—even though it’s not. (The chart actually described these as “Tariffs Charged to the U.S.A.” and added in smaller letters “Including Currency Manipulation and Trade Barriers.”)

So the premise of the Trump policy is not “we charge them in tariffs what they charge us in tariffs” (even though that’s how he has described it). The real premise of the Trump policy is, “Imports are bad, exports are good.”

Would You Give Up Your Imports?

Author Greg Ip (writing in 2010, years before Trump ran for president) comments on this attitude:

We usually think the benefit of international trade is more exports. But that’s a blinkered view. Imports are just as important, perhaps more important, because they enrich consumers. Think of all the things you’d forsake if borders were closed: fresh fruit and tropical flowers in the dead of winter, . . . Harry Potter novels, . . . Hyundais.

Maybe check your own house to see where the things you buy come from.

As I write this, I am wearing a shirt and slacks that were both made in Bangladesh, and a belt made in India. My paper clips are in a holder made in Taiwan. My old-fashioned paper calendar was made in Vietnam. I have some candy in my desk drawer that was made in Germany. Both my favorite brands of highlighters were made in Mexico. My stapler, electric pencil sharpener, desk lamp, portable handheld scanner, and printer/copier were all made in China—as was the new iPhone I just got a few weeks ago. (I do have a three-hole punch that was made in the U.S.A.) And oh yes—my wife and I drive a Hyundai, which comes from Korea.

Would you really be willing to give up all the things you have “imported” from other countries—or pay, say, twice as much for a replacement made domestically?

Ip goes on to summarize,

To economists, the benefits of both exports and imports are so obvious that it’s one of the few things this notoriously fractious profession agrees on. . .

Global trade is one of the great economic success stories. One study . . . estimates the average American household is some $10,000 per year richer thanks to the post-war expansion of trade.”

My Favorite Econ Lesson—“The Law of Comparative Advantage”

I was an Economics major in college (but I have not used that training much since, so I don’t claim to be an expert). One lesson I learned in an Econ class, though, made such an impression that it has stuck with me ever since. So I was glad to see that Ip actually referred to the law of “comparative advantage.” Although less well-known than “the law of supply and demand,” the law of comparative advantage is just as important—at least when it comes to understanding international trade.

You see, one concern some Americans (and President Trump) may have is that if other countries can make virtually every product more cheaply than Americans do, then we will end up importing everything and manufacturing and exporting nothing, leaving Americans with little to do to make a living except flip one another’s burgers. The law of “comparative advantage” explains why this is not the case.

China’s Widgets, America’s Gadgets

Suppose, for example, that there are only two trading partners—China and the U.S.—and only two products that anyone needs to buy. We’ll call them “gadgets” and “widgets.” And suppose that China is capable of producing gadgets at half the cost of American producers, and is also capable of producing widgets at only a tenth of the cost of American producers.

The law of comparative advantage explains why, under this scenario, the policy that would lead to the greatest prosperity for both countries would be for China to produce the world’s widgets and for the U.S. to produce the world’s gadgets (and not for China to produce everything). This is because, although China has an absolute advantage in the production of both goods, its “comparative” advantage is greater in producing widgets; and while the U.S. is at an absolute disadvantage in producing both products, it still has a “comparative advantage” in the production of gadgets (as opposed to widgets). China also needs American consumers to be able to make a living, so that they can buy the things that China does produce.

There is math that you can do to prove that this is the case, and I found it quite amazing when I was an introductory Econ student. Ip describes the same principle without using math:

Countries even benefit by importing something they could make themselves. Why do parents hire a nanny when they could stay home and raise the child themselves? Because it lets them earn the money to buy a nicer home and send the child to college. The same principle of comparative advantage is why rich countries buy toys and clothing from poor countries: so that their own workers can earn more building aircraft, conducting heart bypass operations, or making movies.

The Politics of Trade

Ip does explain, though, why politicians often resist free trade even though economists usually support it:

Free trade is a tough sell because its benefits are less obvious than its costs. Imports make the majority of consumers better off, but they seldom know or care, whereas companies and workers that lose their livelihoods to imports are quick to let their representatives in Congress know. . . .

Before World War II, protectionism was the stated preference of Republican presidents [note how Trump has expressed admiration for William McKinley], which is why Herbert Hoover signed into law the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930. It raised tariffs on thousands of products and triggered outrage and, in some cases, retaliation from other countries. Global trade was already collapsing, but Smoot-Hawley accelerated the process [and thus deepened the Great Depression].

Ip includes one paragraph that probably comes close to explaining the rationale behind the Trump tariffs:

Trade does not make Americans collectively poorer, but it does alter the balance between winners and losers. In the case of the iPod [this was written in 2010; substitute “iPhone” and the principle is the same], the winners, besides Americans who buy iPods, are clearly Steve Jobs and Apple’s employees. . . . The losers are the people who may have assembled iPods in the United States but can’t compete with the low wages paid to factory workers in China. Trade can thus aggravate inequality, eroding wages for formerly middle-class workers while rewarding those at the top. [Indeed, the box for my new iPhone 16e highlights this—it says it was “Designed by Apple in California” but “Assembled in China.”]

Presidents Were More Responsible—Until . . .

Ip notes that one reaction to the Smoot-Hawley tariff disaster was that in 1934, after Franklin Roosevelt became president,

Congress passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. It shifted responsibility for trade policy to the president who is less susceptible to narrow, protectionist interests and more likely to see trade agreements as a foreign policy bargaining chip.

At least, it seemed like the president would be “less susceptible [than Congress] to narrow, protectionist interests” until Donald Trump became president. (Whether he is open to using his tariffs “as a foreign policy bargaining chip” is something that seems to swing back and forth by the day.)

As you may guess, I think that on balance free trade is to be preferred to protectionism, and thus that the Trump tariffs are a bad idea. The subtitle of Ip’s chapter in international trade is, “The Globalization Game Is Here Whether We’re Ready or Not.”

From the Rink to the Parking Lot

The main title of the chapter, though, is “Drop the Puck!” Where does that come from? Ip says this:

World trade is like hockey: fights are inevitable, but they’re more dangerous when the players leave the rink and settle matters in the parking lot. Like the referee who hands out the penalties and lets the game continue, the WTO [World Trade Organization] gives countries an impartial venue to settle their trade disputes rather than mixing it up in the parking lot.

In all the talk about Trump’s tariff policy, we’ve heard very little about the WTO. It seems like Donald Trump is determined to mix it up in the parking lot.